Vote for what matters to you

What issues do you think need attention, resources, and collaborative action?

50 votes

There are ten subtopics for

in Houston

Risks

26

Federal disaster declarations in Greater Houston in 41 years.

Climate disasters in the form of hurricanes and rain storms pose a serious threat to the Houston region, and the risks are only projected to increase in the future.

In this page we talk about the following:

Natural Disaster Risks in Houston

Exploring natural disaster risks in our region

In the greater Houston region, natural disasters have become more frequent, dangerous and costly. The risks are only projected to increase in the future, threatening Houstonians’ lives and livelihoods.

Why natural disaster risks matter to Houston

Those who live in Greater Houston are all too familiar with the risk of natural disasters in the form of flooding or hurricanes. Hundreds of thousands of properties in the region are currently at risk of flooding, and that figure is only projected to increase over time as storms become more intense and common. This increasing risk poses a threat to the safety of all residents. Without a stronger understanding of our current and future risk, our region’s residents and leaders cannot fully prepare for or mitigate the catastrophic consequences of frequent disasters.

The more we understand the scope of disasters and the effects of climate change in our region, the more we can do to minimize risks to our community.

The data

History of Disasters in the Houston area

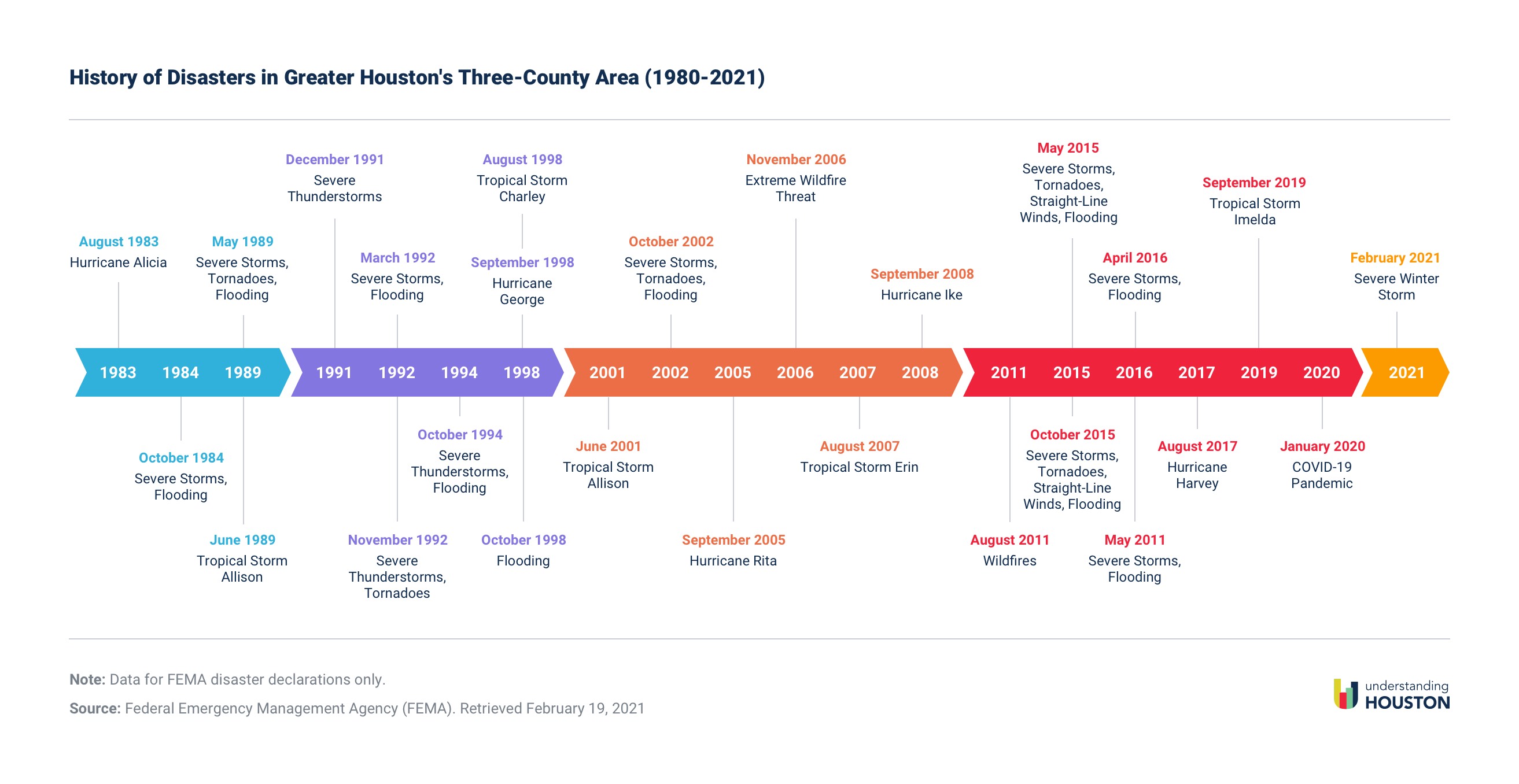

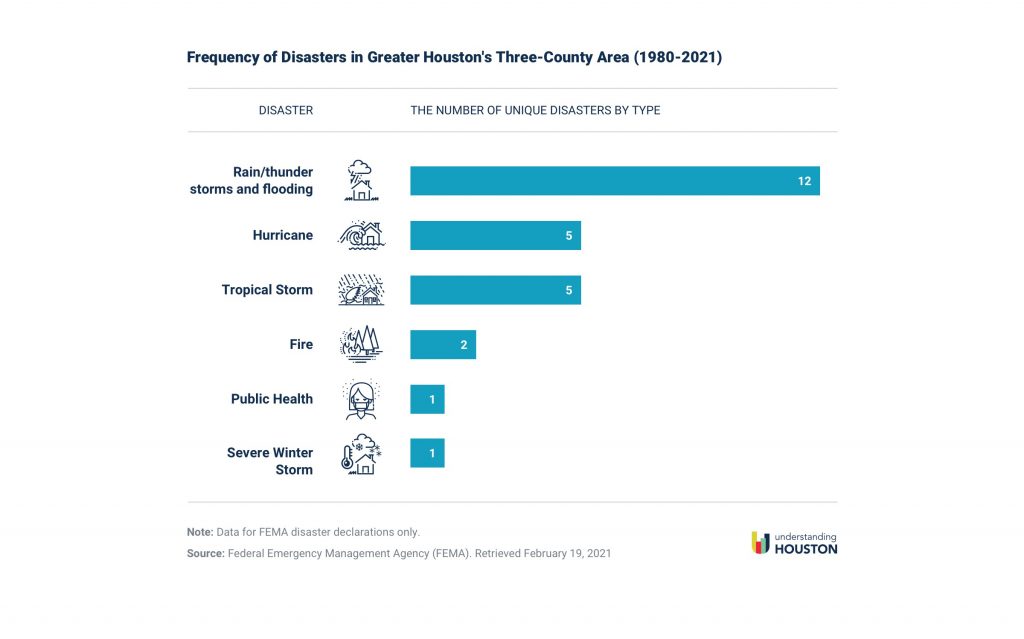

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has declared a disaster in Fort Bend, Harris or Montgomery counties — the three most populous counties in Greater Houston — 26 times in the past 41 years, including the most recent severe winter storm in February 2021. Nearly a third of those (eight) have occurred since 2015.

Since 1980, the Greater Houston region has experienced 12 major rain/thunderstorm and/or flood events, five hurricanes, five tropical storms, two wildfires, a pandemic caused by the new coronavirus, and, most recently a severe winter storm in February 2021 which caused week-long power and water outages, busted pipes, and boil water notices.

The fact that about half of these disasters were caused by unnamed storms would not surprise most residents of the Greater Houston area, where heavy rains and flooding are commonplace.

Flooding risk in the Houston area

FEMA creates flood maps to designate areas lying in different flood zones based on varying levels of risk. Properties identified as having at least a 1% chance of flooding in any given year (also known as the base flood or 100-year flood) are designated as a Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA) — the highest risk. Areas that have a 0.2% annual chance of flooding (a 500-year flood) are considered more “moderate” risk.

However, these maps have limitations that don’t accurately predict where flooding occurs. An analysis of flood claims in southeast Harris County between 1999 and 2009 found that 75% of damages were outside the 100-year flood plain.1 The region experienced five major floods during that time, none of which met the criteria of a 100-year storm. Additionally, a 2012 study across the three decades before Hurricane Harvey found that 47% of flood damage claims made by Harris County residents were outside the 100-year flood zone.2 More than half (55%) of homes damaged in the Tax Day Flood in 2016 were outside the 500-year zone, as were one-third of homes damaged during the Memorial Day Flood in 2015, according to an analysis by the Houston Chronicle. Three out of four homes and apartments in Harris County that flooded during Hurricane Harvey were outside the 100-year flood zone, and half of homes damaged were outside all flood zone designations.

First Street Foundation has developed specialized floodplain maps using a model that expands on FEMA’s current maps. While the FEMA maps are based on risk from a single 1-in-100-year or 1-in-500-year event, First Street’s model considers additional factors, such as rainfall flood risk, current climate risk, and areas not mapped by FEMA.

First Street identified 244,842 properties that are at substantial risk of flooding (located within their 100-year flood area) in the three counties — that’s 56,680, or 30%, higher than current FEMA estimates of 188,162. First Street’s model found 60,411 properties are at risk of flooding in Fort Bend County compared to 13,227 identified by FEMA. This is primarily due to incorporating the chance of levee failure in their models.

Given Houston’s history of flooding well-beyond the designated “high risk” zone, current flood maps haven’t accurately predicted the extent of flooding in the region. The broadest measure of flood risk expands beyond the number of properties within the 100-year flood zone to include those located in floodways, “protected” by levees, and are in the 500-year flood zone. Using this definition, more than 322,000 residential properties (21.7% of all residential properties) in Greater Houston are located in a flood plain.

Harris County has the most residential properties located in a floodplain (234,404), the majority of which are in 500- and 100-year flood zones. In Fort Bend County, where 68,264 residential properties are at some risk of flooding, the majority of those properties are protected only by a levee. Most residential properties in Montgomery County that are at risk of flooding are located in the 500-year flood zone.

In Fort Bend, 29.5% of residential properties are located in all flood areas combined, compared to 21.8% in Harris County and 11.1% in Montgomery County.

Disproportionate flood risks

Research has shown that the communities most vulnerable to flooding are low-income and non-white.3 This is especially true in Houston where these groups have historically lived on low-lying land (a result of decades of discriminatory housing policies), receive fewer flood mitigation projects, and are characterized by decades of disinvestment, such as poor stormwater infrastructure.4 A recent study found that Black and Latino Harris County residents who lived outside the FEMA-designated 100-year flood zone were flooded at disproportionately high rates during Hurricane Harvey.5

This proves particularly challenging as low-income homeowners seek to rebuild or prepare for the next disaster. FEMA’s “50% rule” states that if the cost of improvements or the cost to repair a property exceeds half its [pre-disaster] market value (known as “substantial damage”) it must be brought up to current floodplain management standards. This regulation is particularly challenging for households living in homes appraised at lower values because the typical minimum cost of home repair after a flood is around $25,000. That means homes valued at less than $50,000, for example, are typically out of repair options and at greater risk of further damage when the next storm hits.

More than 32,000 residential properties valued at less than $50,000 are located in flood areas in the three-county region, with the majority being located in Harris County.

In Harris and Montgomery counties, homes that are valued below $50,000 are more likely to be found in a flood area. Across the three-county region, 23.3% of residential properties valued at $50,000 or less are located in flood areas, compared to 21.7% of all residential properties.

Future flood risk

We know that extreme rain poses a growing threat to the Houston area, which means the frequency and intensity of flooding will continue to increase. First Street Foundation projects more properties will flood in the future because of rising sea levels and changing hurricane patterns — consequences of climate change.

The number of properties in Harris County at risk of flooding is projected to increase to 204,513 in 2050 (up 21.7% from 2020). As many as 64,000 in Fort Bend and 17,600 in Montgomery counties are at “substantial” risk of flooding in 2050.

That means potentially one in seven (14.2%) of properties in the three-county region will be at risk of flooding by 2050. That is about one in five properties in Fort Bend, one in seven in Harris, and one in 15 in Montgomery counties — each higher than the rate for Texas overall.

References:

- Blessing, R., Sebastian, A., & Brody, S. (2017). Flood Risk Delineation in the United States: How Much Loss Are We Capturing? Natural Hazards Review, 18, 04017002. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000242.

- Highfield, W.E., Norman, S.A. & Brody, S.D. (2013). Examining the 100‐Year Floodplain as a Metric of Risk, Loss, and Household Adjustment. Risk Analysis, 33: 186-191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01840.x.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Framing the Challenge of Urban Flooding in the United States. https://doi.org/10.17226/25381.

- Chakraborty, J., Collins, T.W., & Grineski, S. E. (February 1, 2019). Exploring the Environmental Justice Implications of Hurricane Harvey Flooding in Greater Houston, Texas. American Journal of Public Health, 109, no. 2: pp. 244-250. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304846.

- Smiley, K.T. (2020). Environmental Research Letters, 15 0940b3. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba0fe.

Maternal & Child Health

23 per 100,000 live births

The maternal mortality rate in Texas between 2018 and 2020 was 22.9 per 100,000 live births — above the national rate of 20.4.

Between 1987 and 2018, maternal mortality in the United States soared 140%. This is largely driven by the disproportionate toll of maternal mortality on Black women, who die from pregnancy-related causes at three times the rate of white women (55.3 and 19.1, respectively).

In this page we talk about the following:

Maternal & Child Health

Pregnant women and children in Houston’s three-county region have poorer health outcomes compared to national averages, jeopardizing the future well-being of mothers and their children

Overall infant and child mortality rates in the region are down, but we’ve seen declines in health and well-being in pregnant women, infant vaccinations and child nutrition over the last decade. Disparities have either widened or remained flat — the result of variation in underlying chronic conditions, disproportionate access to quality health care, and internalized bias in our health care system.

Why maternal and child health matter to Houston

A more vibrant Houston region with opportunity for all is built on a foundation of healthy women, mothers and children. Babies who are born in good health and who continue to thrive with positive experiences, tend to grow into healthy and productive adults who sustain our population and contribute to our economic vitality. Of course, a newborn’s health depends not only on the mother’s health during gestation but also her state of health before pregnancy.

Women who are most likely to have a healthy pregnancy are under 40 years old, are college-educated, have good-paying jobs that provide medical insurance; live in a supportive home in a safe neighborhood with access to parks, clean air and water; and have a supportive social network. However, even among women who check all the boxes, there is no guarantee of a healthy pregnancy or baby.1,2 Black women have significantly higher maternal mortality rates than white women, and babies born to Black mothers have higher mortality rates than babies born to white mothers — even when controlling for a variety of factors such as education3,4 and health conditions.5

The more we know about the health and well-being of mothers, infants and children in the Houston region, the more we can target solutions and interventions to improve the lives of our most vulnerable residents.

The data

Disparities in maternal and child health outcomes across racial/ethnic groups are deep and pervasive

Disparities in maternal, infant and child mortality and health have been evident for many years.6 Women of color, particularly Black women, consistently have the highest maternal mortality rates. Multiple factors contribute to these disparities, such as variation in underlying chronic conditions, access to quality health care, internalized bias and structural discrimination.

For a variety of environmental and social reasons, Black women are more likely to have pre-existing conditions such as obesity, heart disease, and diabetes prior to being pregnant, which increases pregnancy risks and the likelihood of maternal and child health issues.7 Further, the health care they receive is typically of lower quality — not only because of lower-quality health care establishments and caregivers8 but also because of implicit racial bias embedded in the health care system. For example, health concerns and reported pain from Black patients are more likely to be dismissed than those from white people.9 The Listening to Mothers Survey III found that one in five Black and Hispanic women reported poor treatment from hospital staff — citing factors such as race, ethnicity, cultural background or language — compared with 8% of white mothers.10

National data show that Black women are more likely to receive delayed prenatal care (after the first trimester) or none at all.11 While Medicaid covers women who are pregnant, women must first learn they are with child, apply for coverage, and wait to be approved before they are able to seek care. By the time this happens, it could be after the first trimester of gestation.

Black women are also more likely to receive poor follow-up care after the baby’s birth or none at all.12 Nearly 71% of women who died from pregnancy-related causes in Texas in 2013 died within one year after the baby was born, according to a 2020 report from the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee.

Black women have higher maternal mortality rates than white women even when income and education are controlled.13 This phenomenon led some researchers to theorize that extreme emotional and psychological stress can produce a sufficient physiological reaction, called “weathering,” that harms, or ages, the body and could lead to negative health outcomes, including maternal and infant mortality rates.14 Meaning, the compounding trauma and stress simply from being both Black and a woman could contribute to racial disparities and negative outcomes in maternal and child health. This could also explain why the mortality rate for Black mothers over 40 is nearly triple that for white mothers in the same age group.15,16,17

The national maternal mortality rate jumped 37% between 2018 and 2020

One of the more troubling trends in health is the increasing number of women who die from pregnancy-related complications. The World Health Organization defines a pregnancy-related death as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy.

The leading causes of pregnancy-related death in Texas include cardiovascular-related issues, mental disorders, hemorrhaging, and preeclampsia, characterized by extremely high blood pressure.The Texas Department of State Health Services estimates 89% of these deaths in 2013 could have been prevented.

Between 1987 and 2018, maternal mortality in the United States soared 140%. (Because of changes in methodology, data prior to 2018 cannot be compared with data for 2018 and after.)

In 2020, 861 women died of maternal causes (i.e., women who die from pregnancy-related complications while pregnant or within 42 days of giving birth) in the U.S., an increase from 754 in 2019. The maternal mortality rate in 2020 was 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births, up from 20.1 in 2019, and higher still from the 2018 rate of 17.4 — a 37% increase.

Texas’ maternal mortality rate is above the national average

Other wealthy nations are not experiencing the high rates of maternal mortality found in the U.S. In Canada, the maternal mortality rate is about 10 per 100,000 live births, while in the U.K. it is 7. The U.S. trend is also at odds with several less developed countries, where maternal mortality has declined.

The Texas maternal mortality rate in 2018 was 18.5 per 100,000 live births, above the U.S. average of 17.4. When data between 2018 and 2020 are combined, the Texas maternal mortality rate is 22.9 — still higher compared to 20.4 overall in the U.S. Among the 30 states for which a rate was calculated, Texas ranks in the middle, with the highest rate in Arkansas (40.4) and the lowest rate in California (10.2).

Maternal mortality rates vary drastically by both race/ethnicity and age. In 2020, the maternal mortality rate for Black women was 55.3 deaths per 100,000 live births. This is not only nearly three times the rate for white women (19.1), but it is also 1.5 times the rate from two years earlier in 2018 (37.3 deaths per 100,000 live births).

Typically, the younger the woman’s age, the lower the mortality rate. The maternal mortality rate per 100,000 live births was 13.8 for all women under 25 years of age, 22.8 for women between 26 and 39, and 107.9 for women 40 and older. However, Black women under 25 are still 1.5 times more likely to die than white women between 25 and 39 years of age.

Women over 40 face a much higher rate of maternal mortality than women under 40. Black women across all ages experience higher rates of maternal mortality. In 2020, Black women over the age of 40 had a maternal mortality rate of 263.1 per 100,000 live births, nearly triple the rate for white women in the same age group (96.8).

What is maternal morbidity?

The World Health Organization defines maternal morbidity as any health condition attributed to and/or aggravated by pregnancy and childbirth. Maternal mortality can be too small (statistically) to see meaningful trends at smaller geographies, so researchers often cite severe maternal morbidity. Severe maternal morbidity can be considered “a near miss” for maternal mortality and refers to unexpected outcomes of labor and delivery resulting in significant short- or long-term consequences to a woman’s health.18

Between 2008 and 2015, Harris County’s incidence of maternal morbidity increased 53%, compared to a 15% percent increase for Texas overall. In order to address this rise in Texas, in 2021 lawmakers passed a bill expanding postpartum Medicaid coverage from two months to six months, but many advocates hoped for a full year of health coverage to reflect the long-term impact of giving birth on a woman’s body. Similar to maternal mortality, maternal morbidity in Texas has significant variation in rates across racial/ethnic groups.19

Pregnant women in Fort Bend and Harris counties access prenatal care in their first trimester at lower rates than the state and nation

Early prenatal care is defined as pregnancy-related care beginning in the first trimester (1-3 months). It has been viewed as a strategy to improve pregnancy outcomes for more than a century.

Nationally, less than 2% of pregnant women received no prenatal care during their pregnancy in 2020. In Texas, the rate was double at 4%. In the three-county area, the rate of no prenatal care ranged from 5.6% in Harris County to 3.2% in Fort Bend and 1.5% in Montgomery in 2020.

While none of the three counties is considered maternity care deserts, a lack of health insurance is the largest contributor to women delaying or not accessing prenatal care.20 While Medicaid covers women who are pregnant, women must first learn they are with child, apply for coverage, and wait to be approved before they are able to seek care. By the time this happens, it could be after the first trimester of gestation. In an analysis of national data, researchers found women with Medicaid were less likely to begin prenatal care in the first trimester and were less likely to receive adequate prenatal care compared to privately insured women.21

More than 77% of pregnant women in the U.S. received prenatal care in the first trimester in 2020, unchanged since 2016. While early prenatal care has slightly increased recently in Texas to nearly 70% in 2020 from 67% in 2016, it remains below the national rate. In fact, Texas was ranked last in the country for early prenatal care in 2016, according to the most recent report on the topic from National Center for Health Statistics.

Regionally, pregnant women in Montgomery County receive early prenatal care at higher rates, 73% compared to 60% in Fort Bend and Harris counties. The rate of early prenatal care in Harris County has not improved since 2016, and the rate in Fort Bend has declined by more than 10 percentage points from 2019 to 2020.

Overall infant mortality in the Houston-area has ticked down in the last decade, though racial disparities have widened

Infant mortality is defined as the death of a baby before their first birthday, and it is regarded as a strong indicator of the overall health of a population. The five leading causes of infant death are congenital malformations, low birth weight, maternal complications, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and unintentional injuries. The health of the mother, level of prenatal and postnatal care, and access to health care also influence infant mortality.22

Infant mortality rates are highest among infants born to teenage moms and women over 40. Babies born to mothers with obesity or mothers who smoke or consume alcohol during pregnancy also have a greater risk of infant mortality, particularly during the first 28 days after birth.23,24,25

The infant mortality rate in the United States was 5.6 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2019. Despite the progress made to reduce infant mortality in the past decades, the national rate is still higher than that of other developed countries. Data from Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shows the 2021 infant mortality rate in the U.S. is higher compared to several nations, including Russia, Canada, the Netherlands, France, Poland, United Kingdom, South Korea, and Estonia.

What is the infant mortality rate in Texas? Houston’s three-county region?

Infant mortality in Texas was 5.6 per 1,000 live births in 2017–19, slightly lower than the national average. Locally, the highest infant mortality rate is in Harris County, and the lowest rate is in Fort Bend County. While infant mortality rates over the past decade have dipped in Texas, they have remained relatively flat in Harris County. Wide disparities exist among racial groups, for many of the same reasons described above.

In Harris County, the infant mortality rate for babies born to Black mothers is three times that for babies born to white women. While the infant mortality rate in Harris County for white women has remained relatively flat, it has worsened for Black women — up 26% between 2011 and 2018. The racial disparity in infant mortality rates in Harris County is nearly 1.5 times the gap at the state and national level.

Among the three regional counties, the mortality rate in 2018 for babies born to Black mothers was highest in Harris County (11.19 per 1,000 live births) compared to the nation (10.6) and Texas (9.9). This is different from what we see among white mothers. The mortality rate in 2018 for babies born to white mothers was lowest in Harris County (3.7 per 1,000 live births) compared to Texas (4.5) and the nation (4.5).

Continue reading about disparities in life expectancy in Texas and how it varies across neighborhoods in Houston’s three-county region.

Babies born to mothers in Fort Bend and Harris counties tend to have the lowest birth weights in the region

Newborns weighing less than 2,500 grams, or 5.5 pounds, are considered low birth weight. In addition to the high risk of infant mortality, infants with low birth weight also face short- and long-term health conditions that can permanently affect their quality of life, such as intestinal disorders, learning and behavioral problems, and type 2 diabetes.26,27

The most common causes of low birth weight are premature birth (birth prior to 37 weeks gestation) and restricted fetal growth (when a fetus is smaller than expected for its gestational age). Environmental risk factors contribute to fetus development — exposure to air pollution (both indoor and outdoor) and drinking water contaminated with lead are also found associated with low birth weight.28 This has significant implications since communities of color and low-income communities are more likely to be exposed to contaminated air and water, due to years of systemic environmental racism. Additional risk factors such as smoking or drinking alcohol during pregnancy may also lead to slower fetus development even if the baby was born full-term.

Continue reading about water and air pollution in Houston.

Nationally, the percentage of infants born with low birth weight has ticked up slightly to 8.24% in 2020 from 8.15% in 2010. Regionally, 8.26% of babies in Fort Bend County, 8.72% in Harris County, and 6.79% in Montgomery County were born with low birth weight in 2020. Low birth weight is more prevalent among babies born to Black women than those born to Hispanic or white women, even when controlling for education, according to a national analysis.29 Again, this can be attributed to many of the same aforementioned reasons.

Vaccination rates in Houston and Texas have fallen while they have risen nationally

Immunization is a safe and cost-effective means of preventing illness in young children and interrupting disease transmission within the community.

The seven-vaccine series provides immunization against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, poliovirus, measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis b, hemophilus influenza b, chicken pox, and pneumococcal infections. The seven-vaccine series indicator measures overall compliance with the recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for young children.

For children born in 2017 and 2018, the seven-vaccine coverage rate by age 24 months was 70.5% in the U.S. In Texas, the rate was lower at 65.9%, and in the city of Houston, the rate was 65.2%.

Coverage by age 2 was lower for most vaccines among children who did not have private health insurance. Coverage was lower for both Black and Hispanic children compared with white children for most vaccines. The lowest coverage was for the influenza vaccine (60.6%).30 Research suggests racial disparities in vaccine uptake could be due to overall lower insurance rates, apprehensions or distrust of the health care system, or misconceptions about vaccine efficacy.31

Child mortality rates are highest in Harris County and lowest in Fort Bend

Because of advances in medicine over the last half of the 20th century, child mortality has declined so much that even though youth comprise a quarter of the U.S. population, they represent less than 2% of all deaths.32 The leading causes of death among children and adolescents include accidents, assaults, suicide, and cancer.33

In Texas, 48.6 per 100,000 children die before their 18th birthday. Within Houston’s three-county region, child mortality rates are highest in Harris County (51.4 per 100,000) and lowest in Fort Bend (31.6).

Child mortality rates for Black youth are consistently the highest compared to other race/ethnicity groups. Mortality rates in Harris County among Black children are the highest (96.5 per 100,000) — nearly 2.5 times that of white children. Even with the overall decline in child mortality in the U.S., racial disparities continue and are greatest for certain medical conditions that are sensitive to delays in medical care, suggesting poor access to health care and mental health care in the Houston area.34

Nearly 232,000 Houston-area children do not have health insurance

Goals for maternal and child health don’t end after the postnatal period. While maternal and child health is focused on the health of mothers during pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period — defined as up to one year after birth, the field of study also covers a child’s health during these stages and the first five years of life — the most important time of early childhood development.

Children may receive health insurance coverage from a variety of sources, including private insurance or public programs such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). However, some have no insurance at all. In 2020, 4.3 million American children under the age of 19 did not have access to health insurance coverage.

Nearly one million children in Texas do not have any form of health insurance coverage — about one in eight. Nearly 232,000, or 23%, of Texas’s uninsured children reside in Houston’s three-county region. The level of uninsured children in the Houston area (13.6%) is slightly higher than in Texas (12.8%), which is double that of the nation overall (5.7%). Fifteen percent of children in Harris County do not have insurance — the highest rate in the region — compared with 9.1% of children in Fort Bend and Montgomery counties.

Consistent with coverage trends among adults, Hispanic children in the Houston region have the highest uninsured rates. One out of five Hispanic children in Harris County does not have health insurance compared to one out of 15 white children. One out of eight Black children in Montgomery County does not have health insurance.

Children from low-income families may be able to get access to health insurance coverage through Medicaid and CHIP.

On average in 2020, 3.2 million children in Texas were enrolled in Children’s Medicaid and CHIP. The COVID-19 pandemic caused an increase in Medicaid/CHIP enrollment across the country. Texas saw a 23% increase in Medicaid/CHIP enrollment from February 2020 to September 2021. In State Fiscal Year 2020,35 nearly 633,000 children enrolled in Medicaid, and 80,000 children enrolled in CHIP each month in the three-county region.

Food insecurity among children was in decline prior to the pandemic

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines food insecurity as a lack of consistent access to adequate food for a healthy life. Children who do not have enough to eat tend to experience lifelong health problems. Food insecurity has been found to not only have clear and consistent harmful impacts on children’s general health, chronic health, and acute health,36 but also on their physical, behavioral and brain development.37

Feeding America provides estimates for food insecurity at different community levels. Using the relationship between food insecurity and its closely linked indicators (poverty, unemployment, homeownership, disability prevalence, etc.) an estimated food insecurity rate is generated.

In 2020, 11.7 million (16%) children in the U.S. were food insecure, a rate higher than the general population (11.8%).38

According to Feeding America, child food insecurity in the Houston area fell from 2017 to 2019. However, the effects of COVID-19 were estimated to have led to an increase in food insecurity in 2020, which remained elevated in 2021. Feeding America estimates one in four children in Harris County are food insecure — about a quarter of a million children.

More than a third of City of Houston and Texas high school students are overweight or have obesity

Even when children have enough to eat, they may have poorer nutrition or eat lower-quality food as budget constraints may prompt families to purchase cheaper, more energy-dense foods.39 Childhood obesity is defined as having a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile for their gender, according to the CDC sex-specific BMI-for-age growth charts. About 18.5% or 13.7 million children and adolescents in the United States have obesity, putting them at higher risk for poor health.40

In 2018, the obesity rate in Texas for children who are 2-4 years old and are enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) was 15.9%. While this is one percentage point lower than the 2010 rate, it remained above the national level of 14.4%.

The percentage of American high school students who are overweight ticked up from 15.2% in 2011 to 16.1% in 2019. In Texas, that rate increased nearly two percentage points to 17.8% during the same period. About 18.8% of high school students who live within the city of Houston are classified as overweight. Obesity rates in Houston grew faster than the rate of those who are overweight — an additional 19.5% of high school students have obesity, an increase of six percentage points since 2011. Combined, 38.3% of high school students in Houston are either overweight or have obesity compared to 34.7% in Texas and 31.6% nationally.

More Helpful Articles by Understanding Houston:

- Houston is Generous

- Houston is Engaged

- The Big Picture Event | Fort Bend County

- Ending Homelessness in Houston

- How Big is Houston?

References:

- Nelson, A. (2002). Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of the National Medical Association, 94(8), 666.

- Martin, N., & Montagne, R. (2017). Nothing protects black women from dying in pregnancy and childbirth. ProPublica, December, 7, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/nothing-protects-black-women-from-dying-in-pregnancy-and-childbirth

- Schoendorf, K. C., Hogue, C. J., Kleinman, J. C., & Rowley, D. (1992). Mortality among infants of black as compared with white college-educated parents. New England Journal of Medicine, 326(23), 1522-1526.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. (2016). Severe Maternal Morbidity in New York City, 2008–2012. New York, NY. Retrieved from https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/maternal-morbidity-report-08-12.pdf

- Tucker, M. J., Berg, C. J., Callaghan, W. M., & Hsia, J. (2007). The Black-White disparity in pregnancy-related mortality from 5 conditions: differences in prevalence and case-fatality rates. American Journal of Public Health, 97(2), 247–251. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.072975

- Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths — United States, 2007–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:762–765. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6835a3external

- Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee and Department of State Health Services Joint Biennial Report (Sep 2020, Rev. Feb 2022). Retrieved from https://www.dshs.texas.gov/legislative/2020-Reports/DSHS-MMMRC-2020.pdf

- Howell, E. A., Egorova, N., Balbierz, A., Zeitlin, J., & Hebert, P. L. (2016). Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 214(1), 122.e1–122.e1227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.019

- Nelson, A. (2002). Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of the National Medical Association, 94(8), 666.

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, Applebaum S, Herrlich A. Listening to MothersSM III: Pregnancy and Birth. New York: Childbirth Connection, May 2013. Retrieved from https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/health-care/maternity/listening-to-mothers-iii-pregnancy-and-birth-2013.pdf

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2012, October). Disparities in Health Care Quality Among Minority Women Selected Findings From the 2011 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Essien, U. R., Molina, R. L., & Lasser, K. E. (2019). Strengthening the postpartum transition of care to address racial disparities in maternal health. Journal of the National Medical Association, 111(4), 349-351.

- Martin, N., & Montagne, R. (2017). Nothing protects black women from dying in pregnancy and childbirth. ProPublica, December, 7, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/nothing-protects-black-women-from-dying-in-pregnancy-and-childbirth

- Bryant, A. S., Worjoloh, A., Caughey, A. B., & Washington, A. E. (2010). Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(4), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.864

- Geronimus, A. T. (1992). The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: evidence and speculations. Ethnicity & Disease, 207-221.

- Geronimus, A. T., Hicken, M., Keene, D., & Bound, J. (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826-833.

- Holzman, C., Eyster, J., Kleyn, M., Messer, L. C., Kaufman, J. S., Laraia, B. A., … & Elo, I. T. (2009). Maternal weathering and risk of preterm delivery. American Journal of Public Health, 99(10), 1864-1871.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine, Kilpatrick, S. K., & Ecker, J. L. (2016). Severe maternal morbidity: screening and review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 215(3), B17–B22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.050

- Salahuddin, M., Patel, D.A., O’Neil, M., Mandell, D.J., Nehme, E., Karimifar, M., Elerian, N., Byrd-Williams, C., Oppenheimer, D., & Lakey, D.L. (2018) Severe Maternal Morbidity in Communities Across Texas. Austin, TX: University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler/University of Texas System. https://utsystem.edu/offices/population-health/overview/severe-maternal-morbidity-texas

- Osterman, M.J.K., & Martin J.A. (2018) Timing and adequacy of prenatal care in the United States, 2016. National Vital Statistics Reports,l 67(3). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr67/nvsr67_03.pdf

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). (2018) Access in Brief: Pregnant Women and Medicaid. Washington, DC: MACPAC. Retrieved from https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Pregnant-Women-and-Medicaid.pdf

- Singh, G. K. & Yu S. M. (1995). Infant mortality in the United States: trends, differentials, and projections, 1950 through 2010. American Journal of Public Health, 85(7), 957-964. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.85.7.957

- Meehan, S., Beck, C. R., Mair-Jenkins, J., Leonardi-Bee, J., & Puleston, R. (2014). Maternal Obesity and Infant Mortality: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics, 133(5), 863–871. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-1480

- Salihu, H.M., Aliyu, M.H., Pierre-Louis, B.J. et al. (2003). Levels of Excess Infant Deaths Attributable to Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy in the United States. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 7, 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1027319517405

- O’Leary, C. M., Jacoby, P. J., Bartu, A., D’Antoine, H., & Bower, C. (2013). Maternal Alcohol Use and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Infant Mortality Excluding SIDS. Pediatrics, 131(3), e770–e778. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1907

- Squarza, C., Picciolini, O., Gardon, L., Giannì, M. L., Murru, A., Gangi, S., Cortinovis, I., Milani, S., & Mosca, F. (2016). Learning Disabilities in Extremely Low Birth Weight Children and Neurodevelopmental Profiles at Preschool Age. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00998

- Mi, D., Fang, H., Zhao, Y., & Zhong, L. (2017). Birth weight and type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 14(6), 5313–5320. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2017.5234

- Zheng, T., Zhang, J., Sommer, K., Bassig, B. A., Zhang, X., Braun, J., Xu, S., Boyle, P., Zhang, B., Shi, K., Buka, S., Liu, S., Li, Y., Qian, Z., Dai, M., Romano, M., Zou, A., & Kelsey, K. (2016). Effects of Environmental Exposures on Fetal and Childhood Growth Trajectories. Annals of Global Health, 82(1), 41–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2016.01.008

- Ratnasiri, A. W., Parry, S. S., Arief, V. N., DeLacy, I. H., Halliday, L. A., DiLibero, R. J., & Basford, K. E. (2018). Recent trends, risk factors, and disparities in low birth weight in California, 2005–2014: a retrospective study. Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology, 4(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-018-0084-2

- Hill, H.A., Yankey, D., Elam-Evans, L.D., Singleton, J.A., Sterrett, N. (2021) Vaccination Coverage by Age 24 Months Among Children Born in 2017 and 2018 — National Immunization Survey-Child, United States, 2018–2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70, ;1435–1440. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7041a1external

- Institute of Medicine. (2002) Introduction and literature review. In: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press:21–62.

- Cunningham, R. M., Walton, M. A., & Carter, P. M. (2018). The Major Causes of Death in Children and Adolescents in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(25), 2468–2475. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1804754

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html

- Howell, E., Decker, S., Hogan, S., Yemane, A., & Foster, J. (2010). Declining child mortality and continuing racial disparities in the era of the Medicaid and SCHIP insurance coverage expansions. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2500–2506. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.184622

- September 1, 2019 through August 31, 2020

- Thomas, M. M. C., Miller, D. P., & Morrissey, T. W. (2019). Food Insecurity and Child Health. Pediatrics, 144(4), e20190397. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0397

- Gallegos, D., Eivers, A., Sondergeld, P., & Pattinson, C. (2021). Food Insecurity and Child Development: A State-of-the-Art Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 8990. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178990

- Coleman-Jensen, A., Rabbitt, M. P.,. Gregory, C. A., and Singh, A. (2021). Household Food Security in the United States in 2020, ERR-298, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102076/err-298.pdf?v=8785.8

- Thomas, M. M. C., Miller, D. P., & Morrissey, T. W. (2019). Food Insecurity and Child Health. Pediatrics, 144(4), e20190397. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0397

- Hales, C. M., Carroll, M. D., Fryar, C. D., Ogden, C. L. (2107) “Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016.” CDC National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) data brief, 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db288.pdf

Vulnerability & Impacts

3.4 million residents

in the three-county region live in a census tract with at least medium-high vulnerability to disaster impacts.

The impacts of natural disasters are far-reaching and affect our entire region. However, some communities are hit harder than others.

In this page we talk about the following:

Vulnerability to and Impacts from Disasters

Exploring unequal effects of natural disasters on Houston communities

Natural disasters have impacted hundreds of thousands of families in Greater Houston over the past 40 years. Non-white and low-income communities are not only more vulnerable to the impacts of disasters but also are disproportionately affected in significant ways.

Why measuring vulnerability to the impacts of natural disasters matters to Houston

Disasters affect people’s lives in many different ways — financially, physically, emotionally and more — and the effects can linger well after the storm passes. However, not everyone is affected in the same way. Research has shown that some populations and communities are disproportionately affected by natural disasters. Just as one’s ability to fight an illness depends a good deal on the health of the individual, a community’s ability to defend itself from negative shocks caused by a disaster largely depends on its economic, demographic and social health before a storm hits. Black, Latino, low-income and immigrant communities are more vulnerable to the stresses and shocks caused by natural disasters — the result of discrimination, economic and racial segregation, disinvestment, and other challenges – both past and present.

The more we understand about which communities are hardest hit by disasters and in what ways, the better job we can do to prioritize resources to strengthen communities before disasters strike.

The data

Social vulnerability to disasters in the Houston area

Before diving into the data on social vulnerability in Houston, let’s define what it means to be socially vulnerable. How does FEMA define vulnerability? FEMA defines social vulnerability as the susceptibility of social groups to the adverse impacts of natural hazards, including disproportionate death, injury, loss, or disruption of livelihood.

The extent to which natural disasters affect households depends largely on their situation before disaster strikes. Non-white, low-income and immigrant families typically report impacts from disasters that are more severe than those experienced by white, higher-income and native-born families. In part, this is because these groups tend to have lower levels and quality of economic and job security, housing stability and conditions, health insurance coverage, and financial windfall, even prior to a disaster. At the same time, the neighborhoods impacted most are those that were established by segregation, are typically located in low-lying areas, and have experienced decades of disinvestment.1 When disaster comes, these challenges are only exacerbated.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) measures the social vulnerability of counties and census tracts on a scale from 0 (indicating the lowest vulnerability) to 1 (highest vulnerability). Research suggests counties with high vulnerability tend to be less resilient to hazards or shocks and have higher levels of human and economic suffering and loss.2 Part of this is associated with the level of access to resources needed to prepare for, cope with and recover from disasters.

Among Houston’s three most populous counties, Harris County’s SVI is the highest at 0.72, meaning that it is more vulnerable to the negative effects of disasters than 72% of counties across the nation. Fort Bend (0.29) and Montgomery (0.39) counties are less vulnerable by comparison. Their overall vulnerability relative to other counties remained relatively flat between 2014 and 2018.

A total of 3.4 million residents — or 58% — in the three-county region live in a census tract with at least medium-high vulnerability (greater than 0.5). In Harris County, almost 3 million residents, or 64% of the population, live in a census tract that is more vulnerable than half the census tracts in the nation. In Fort Bend County, 239,110 residents (32%), and in Montgomery County, 247,766 (45%), live in census tracts with medium-high vulnerability or higher.

View your neighborhood’s Social Vulnerability Index ranking with the map below.

What makes a person vulnerable to disasters?

The SVI comprises 15 demographic characteristics and social factors across four themes: socioeconomic status, household composition and disability, non-white status and language, and housing and transportation. Examples of vulnerabilities that increase a community’s SVI (i.e., indicating more vulnerability to impacts from disasters), include higher proportions of residents living in poverty, residents older than 64 years or younger than 18 years, non-white residents, and those with poor housing conditions and unreliable transportation.

One of the strongest determinants of community resilience is income and wealth. Higher-income communities are most likely to have access to resources that mitigate disaster impacts and facilitate recovery, allowing residents to be able to move on from disasters relatively swiftly. However, income is only part of the equation. Families of four that earn the median income for the region can still be economically insecure after incorporating the high costs of housing, transportation and other necessities.

Vulnerable households are more likely to experience food insecurity in times of disaster as food prices increase, food availability diminishes from disrupted supply chains, and public transportation halts. Of course, households with more disposable income that can regularly stock non-perishable goods, hygiene products and water are less likely to feel these impacts.

Fort Bend’s medium-low overall vulnerability index masks the fact that the county’s substantial non-white population could be at higher risk of vulnerability to disaster impacts. Any disaster preparedness plan in Fort Bend County should include protocols to target its residents who are potentially more vulnerable to disaster because of limited English language skills and/or social capital to call upon for help. Montgomery County reports higher social vulnerability than Fort Bend on household composition/disability and housing. Harris County is more vulnerable than the other two counties on all measures.

Read more about disaster relief in Houston.

Financial impacts of disasters in the Houston area

To address urgent basic needs, the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) provides housing vouchers or cash directly to those affected through its Individual and Household Program (IHP), which is used to cover expenses caused by the disaster, including medical care, dental care, child care, funeral and burial costs, essential household items, clean-up items, moving and storage costs, and vehicle maintenance. Typically, the number of IHP requests from residents to FEMA indicates the scope of impact and need after a disaster.

More than half a million households across the three-county area applied for FEMA assistance in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, compared to 104,000 after Hurricane Rita and 442,000 following Hurricane Ike. The majority of those seeking assistance after Hurricane Harvey were renters, whereas more homeowners sought assistance after Hurricane Ike. The number of households seeking assistance after floods and tropical storms is smaller than after hurricanes, and homeowners typically make up the majority of requests.

However, not all households that request assistance from FEMA receive it. Low-income households are less likely to receive government assistance.3 One reason for this is that FEMA uses the home’s value before the disaster to determine the level of assistance. If homes have “substantial damage” after the storm combined with “pre-existing” conditions, they are less likely to receive funding for repairs.

The approval rate in the three-county area rarely rose above 50% for most disasters occurring since 2005, and homeowners were more likely to be approved than renters in seven of the last nine disasters. Approval rates for both homeowners and renters are lower in Harris County than in Fort Bend or Montgomery counties.

Three out of five Harris County residents reported financial challenges after Hurricane Harvey, according to a survey conducted one year after the storm by the Episcopal Health Foundation in partnership with the Kauffman Family Foundation. About 51% of white residents experienced financial struggles, compared to nearly 64% of Latinos and 75% of Black residents. One year later, 31% of Black respondents reported being in a worse financial position, compared to 25% of whites, as a result of the hurricane.

Housing impacts of disasters in the Houston area

FEMA provides data on the average cost of damage homeowners experience after disasters, regardless of whether the agency provides financial assistance to rebuild or repair.

Homeowners in the three-county region experienced damage at an average cost of $8,937 after the Memorial Day Flood in 2016, which caused the most damage to homeowners in Fort Bend County. Montgomery County homeowners experienced the most damage from the 2016 Memorial Day Flood and Tropical Storm Imelda. The average damage in Harris County was highest for Tropical Storm Erin and the 2016 Memorial Day Flood.

Slightly more than 8% of Harris County respondents who were displaced by Hurricane Harvey were still living in a temporary shelter a year later, according to the Episcopal Health Foundation Survey. Many returned home to find an unlivable space and reported their current living conditions were not safe. Nearly three out of 10 households with incomes less than 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) cited unsafe living conditions, compared to one in 10 households with higher incomes. Hispanic residents of the 24-county area also reported higher rates of unsafe living conditions due to damage from Hurricane Harvey.

Environmental impacts of disasters and public health in the Houston area

Environmental impacts from flooding and other natural disasters in Houston’s three-county region can have significant effects on public health, both short-term and long-term. Sewage, debris and chemicals mix with flood waters.4 Chemicals known to be carcinogenic and gasses that worsen respiratory problems are released into the soil, water and air.

Water Quality

Rising water levels, flooding and heavy rainfall can carry pollutants into water bodies, residential homes and potable water supply.5 Sewage plants, for instance, are often located in low-lying areas, and are susceptible to flooding.6 When these plants or streets flood, sewage discharges into the flood water. The same happens when refineries and chemical plants are flooded — industrial waste from factories mixes with the flood water.7 Contaminated flood water flows into streets, streams and rivers, and also infiltrates groundwater.

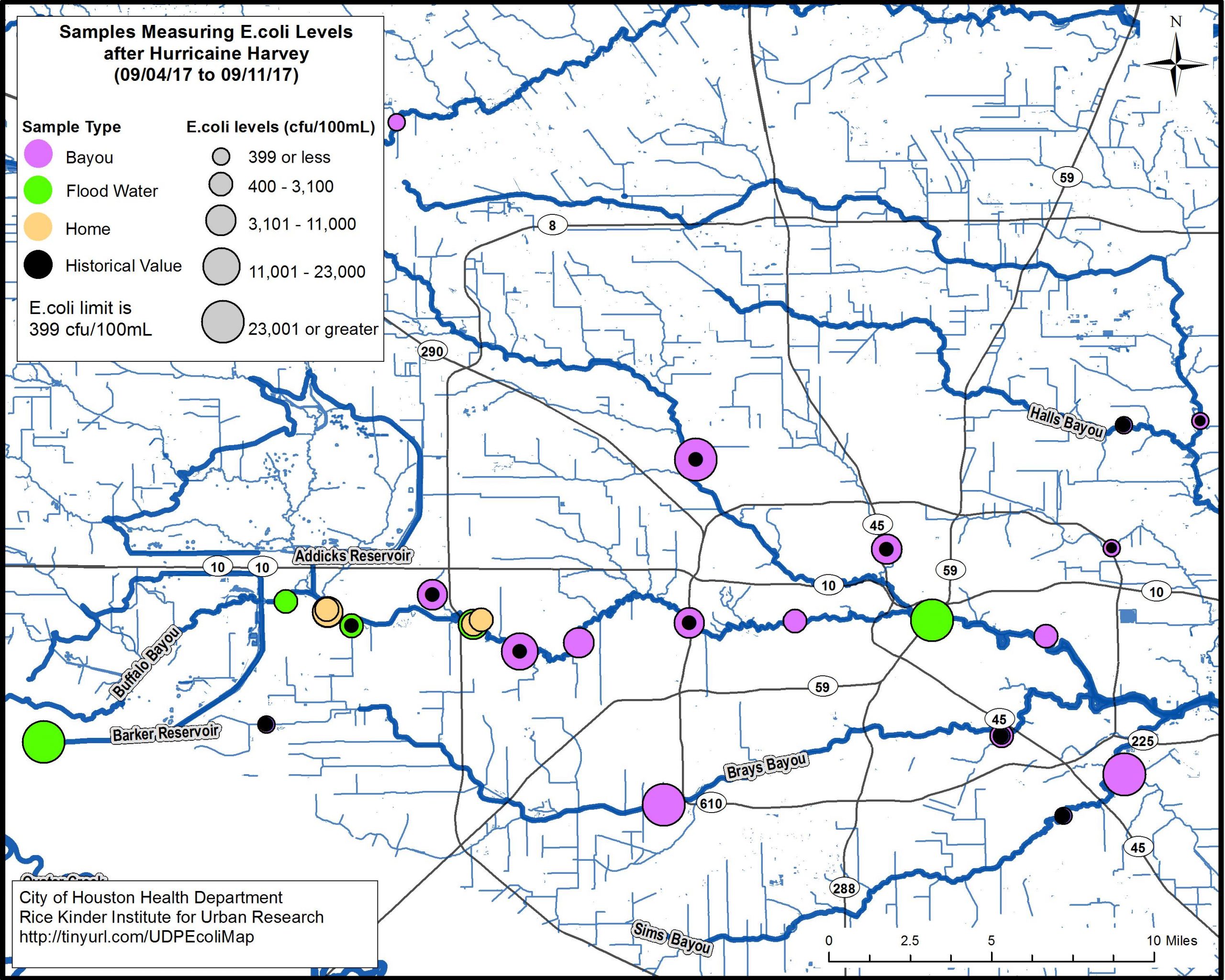

During Hurricane Harvey in August 2017, thousands of gallons of sewage mixed with the one trillion gallons of rain dumped on the region, resulting in high levels of E. coli contamination in local bayous and creeks, neighborhood streets, and residents’ living rooms.8 The map below shows the results for 37 water samples, taken between September 4 — 11, 2017 from surface water, flood water, and the interior of homes across Harris County.

E. coli levels were much lower before Harvey (denoted by black circles), indicating the significant impact hurricanes and flooding can have on water quality. Large purple, green, and yellow circles indicate post-Harvey E. coli levels far greater than the limit set by Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). In some cases, contamination levels were more than 57 times above the acceptable limit. This is especially evident along Buffalo Bayou and in Southeast Houston outside the 610 Loop where levels were far above the limit (23,000 cfu/100mL or greater as opposed to the limit of 399 cfu/100mL).

Air Quality

Air pollution in the greater Houston area can worsen during major storms and hurricanes as oil refineries and chemical plants often conduct emergency shutdowns in preparation and then restart systems after the storm passes. This process involves burning excess fuels and chemicals in the pipelines which emits volumes of pollution into the air. At the same time, air quality monitoring has often been suspended in anticipation of a major storm to prevent equipment damage and can take days to get back online. This makes it difficult to track the exact amount of air pollution emitted during a storm.

Industrial facilities in Greater Houston generated an additional 340 tons of toxic air pollution during Hurricane Harvey because of shutdowns, restarts and malfunctions.9 This figure is likely an undercount since facilities self report the data and it includes only 13 of nearly 400 major industrial facilities operating in Harris and Jefferson counties, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Houston Advanced Research Center mapped the environmental impacts of Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and found significant increases in water and air pollution in the region.

Public Health

The cumulative effect of environmental hazards such as contaminated water and air can negatively affect one’s health immediately after a natural disaster and for an extended period of time afterward. Ingesting contaminated water can make us sick and a surge in air pollution can precipitate or aggravate respiratory conditions — or worse in more severe cases.

Not all physical health conditions that present after a natural disaster are caused by polluted water and air. Residents whose homes flood face unique hazards such as mold exposure or adverse effects sustained during clean-up activities. Mold typically grows on damp surfaces within 24 to 48 hours — and even faster in humid climates.10 Mold exposure affects everyone differently depending on the type and level, but typical symptoms include respiratory problems, nasal/sinus congestion and eye, nose, throat irritation.

After Hurricane Harvey, the Texas Flood Registry found that 63% of respondents experienced at least one negative health symptom such as runny nose, headaches/migraines, problems concentrating, shortness of breath, or skin rash. For the two storms surveyed after Harvey — the May 2019 storms and Tropical Storm Imelda — the results were less severe. Tropical Storm Imelda resulted in negative health symptoms for 9% of respondents, while 8% experienced negative health symptoms after the May 2019 storms.

Low-income communities in predominantly-Black and Latino neighborhoods are disproportionately subjected to environmental hazards and resulting public health problems.11 Communities of color and low-income residents are more likely to reside in Houston areas that flood or contain petrochemical plants because of historical discriminatory housing policies, such as redlining, among other factors.12 These neighborhoods also tend to lack effective wastewater infrastructure, exacerbating flooding risks. As more-intense storms are forecasted, health risks will only increase for Houstonians.

Mental health impacts of disasters in the Houston area

In addition to negative physical health outcomes, disasters hurt residents’ mental health.13

Nearly one-third of Harris County residents experienced negative effects on their mental health after Hurricane Harvey, according to the Episcopal Health Foundation Harvey survey.14 Black residents were most likely to report experiencing negative mental health. And individuals with lower incomes experienced more mental health distress than their higher-income counterparts. To make matters worse, only a small proportion received mental health services in the year following the storm. Latinos were least likely to receive help for mental health distress.

For recent, less intense storms, the Texas Flood Registry still found negative emotional impacts. In the three-county area, 27% of respondents to the Tropical Storm Imelda survey experienced negative emotional changes, while 20% also experienced negative mental health outcomes as a result of the May 2019 storms. An overwhelming majority of respondents in both surveys indicated that their mental health change was due to their experiences during Hurricane Harvey. In other words, mental health outcomes are tied to previous disaster experiences and have a long-term effect. Each new storm may exacerbate negative mental health outcomes from previous storms.15

The mental health impact of exposure to disasters, however, is not limited to storms. In mid-December 2021, almost two years after the arrival of COVID in Houston, more than 20% of Houston MSA residents reported that they felt nervous, anxious or on edge for at least more than half the days of a week.

Helpful Articles by Understanding Houston:

- Houston is Generous

- Houston is Resilient

- Houstonians’ Experiences with Hurricane Harvey and the COVID-19 Pandemic

- After Six Federal Disasters in Five Years, Why Do We Not Fully Prepare?

- Houston is Big

References:

- Smiley, K.T. (2020). Social inequalities in flooding inside and outside of floodplains during Hurricane Harvey. Environmental Research Letters, 15(9). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba0fe

- Bergstrand, K., Mayer, B., Brumback, B., & Zhang, Y. (2015). Assessing the Relationship Between Social Vulnerability and Community Resilience to Hazards. Social Indicators Research, 122(2), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0698-3

- National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2020). Fixing America’s Broken Disaster Housing Recovery System. https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/Fixing-Americas-Broken-Disaster-Housing-Recovery-System_P1.pdf

- Chakraborty, J., Collins, T.W., & Grineski, S. E. (2019, February 1). Exploring the Environmental Justice Implications of Hurricane Harvey Flooding in Greater Houston, Texas. American Journal of Public Health 109, no. 2: pp. 244-250. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304846

- UNC- Asheville Environmental Quality Institute. (2006, January). Assessment of Water Quality Impacts of Hurricanes in Western North Carolina Through Strategic Monitoring and Statistical Analysis (Technical Report No. 06-153). http://www.environmentalqualityinstitute.org/vwin/pdf/Hurricane-Project-EQI.pdf

Schaffer-Smith, D., Myint, S. W., Muenich, R. L., et. al. (2020). Repeated Hurricanes Reveal Risks and Opportunities for Social-Ecological Resilience to Flooding and Water Quality Problems. Environmental Science & Technology, 54 (12), 7194-7204. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b07815 - Yu, P., Zaleski, A., Li, Q., He, Y., Mapili, K., Pruden, A., Alvarez, P. J. J, & Stadler, L. B. (2018). Elevated Levels of Pathogenic Indicator Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes after Hurricane Harvey’s Flooding in Houston. Environmental Science & Technology letters, 5, 481-486. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00329

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2019, February). Watersheds, flooding, and pollution. https://www.noaa.gov/education/resource-collections/freshwater/watersheds-flooding-and-pollution

- Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. (2017, December). Wastewater: Hurricane Harvey Related Sanitary Sewer Overflows and Other WW Discharges. https://www.tceq.texas.gov/assets/public/response/hurricanes/sso-ww.pdf

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2019, December). EPA Needs to Improve Its Emergency Planning to Better Address Air Quality Concerns During Future Disasters (Report No. 20-P-0062). https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-12/documents/_epaoig_20191216-20-p-0062.pdf

- U.S. Federal Emergency Management Administration. Dealing With Mold and Mildew in your Flood Damaged Home. https://www.fema.gov/pdf/rebuild/recover/fema_mold_brochure_english.pdf

- Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, Health Policy Institute. (2008). Environmental justice through the eye of Hurricane Katrina. https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/media/_media/pdf/key_issues/Environment_policy.pdf

Villalón, J. (2020, September 18). Flooding Disproportionately Impacts People of Color. Bayou City Waterkeeper. https://bayoucitywaterkeeper.org/flooding-disproportionately-impacts-people-of-color/ - Flores, A. B., Collins, T. W., Grineski, S. E., & Chakraborty, J. (2020). Disparities in Health Effects and Access to Health Care Among Houston Area Residents After Hurricane Harvey. Public Health Reports, 135(4), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354920930133

- Stanke, C., Murray, V., Amlôt, R., Nurse, J., & Williams, R. (2012). The effects of flooding on mental health: Outcomes and recommendations from a review of the literature. PLoS currents, 4, e4f9f1fa9c3cae. https://doi.org/10.1371/4f9f1fa9c3cae

- Experienced any of the following since and as a result of Harvey: They have had a harder time controlling their temper; Their mental health has gotten worse; They started taking a new prescription medicine for problems with mental health; or Their use of alcohol increased.

- Lowe, S. R., McGrath, J. A., Young, M. N., Kwok, R. K., Engel, L. S., Galea, S., & Sandler, D. P. (2019). Cumulative Disaster Exposure and Mental and Physical Health Symptoms Among a Large Sample of Gulf Coast Residents. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(2), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22392

Response & Recovery

$87,000 wealth gap

Disasters between 1999 and 2013 contributed $87,000 to the Black-white wealth gap in Harris County.

How we respond when natural disasters strike our region has profound effects on recovery time. Unfortunately, not everyone in Greater Houston receives the assistance and resources they need.

In this page we talk about the following:

Response to and Recovery from Disasters

Exploring how our region responds to and recovers from disasters

After disaster strikes, all levels of government, as well as the private sector, respond to provide assistance, though some in our region benefit more than others. The result is that some residents take much longer to recover, if they do at all.

Why an accessible response to disasters matters to Houston

The way in which we respond to disasters affects the total recovery time for a region and, in many cases, whether and how its most vulnerable residents recover, if at all. Many residents receive assistance from the government and have private and personal resources that enable them to make home repairs or rebuild and move on. Others are not so quick to recover, a consequence of experiencing disproportionate impacts combined with difficulty in accessing the resources necessary to rebuild their lives. The results lead to disparate recoveries both in terms of the recovery time and pathways, thereby worsening pre-existing disparities such as the wealth gap.

The more we understand the federal, local and private response and approach to disasters, the better we can identify gaps in assistance delivery for different communities and work to ensure a more equitable and timely response, so that everyone in our region not only recovers but is also made stronger.

The data

Federal response to natural disasters in the Houston area

FEMA’s Individual and Household Program

The Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) addresses urgent basic needs through the Individual and Household Program (IHP), which provides financial assistance to those affected. Thousands apply, but more than half of the applications are denied. Applications that are approved receive varying amounts depending on the extent of damage and disruption, and if property is owned or rented.

The total amount in IHP assistance FEMA distributed after Hurricane Harvey in 2017 dwarfs that of other regional disasters in recent history. Residents of the three-county region received $918.2 million in FEMA disaster assistance as a result of damage from Hurricane Harvey.

FEMA’s IHP program provides assistance to homeowners to repair or rebuild their houses and funding for temporary housing. It also provides funds for owners of multifamily housing complexes, like apartments or condominiums, to fix units. Renters are only eligible for funds for uninsured or under-insured disaster-caused expenses and serious needs, such as repair of personal vehicles, funds for moving and storage, and other miscellaneous expenses approved by the government. Consequently, homeowners typically get more federal financial assistance than renters, who typically receive 64% of the IHP assistance dollars homeowners receive.

The average amount Houston homeowners in the three-county region received after Hurricane Harvey was $6,586, compared to $2,018 for renters. While FEMA paid out more for Hurricane Harvey overall than it did for other disasters, the highest average amount both renters and homeowners received in recent history was for the Memorial Day Flood in 2016. Across all disasters, Fort Bend County residents typically received more than residents of Montgomery and Harris counties.

Small Business Administration

In contrast to the direct aid of FEMA disaster assistance, the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) provides low-interest, long-term loans to homeowners, renters and business owners of all sizes, including nonprofit organizations, that experienced damage from a declared disaster. These loans can be used to cover operating expenses for small businesses as well as repairs and replacement of physical assets that were not previously covered through other means like insurance.

After Hurricane Harvey, the SBA issued $1.5 billion in home loans to residents in the three-county region, which is 50% more than the entire amount FEMA provided ($918.2 million). The three-county region received an additional $116.9 million in home loans for the four flood events in 2015 and 2016 combined.

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), known previously as “food stamps,” helps eligible low-income households buy food and groceries. For up to three months immediately after a declared disaster, SNAP eligibility requirements are expanded to benefit more people.

The greatest uptick in SNAP recipients occurred after Hurricane Harvey. The number of people using SNAP in Greater Houston increased by 50% — from 767,000 in August 2017 to 1,153,000 the following month. SNAP usage increased 53% in Harris County, 44% in Fort Bend County, and 6% in Montgomery County during the same time period.

National Flood Insurance Program

Possession of flood insurance alone does not necessarily translate to a quick recovery,1 but it acts as a safety net. FEMA manages the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) that is designed to compensate for damage from natural disasters. NFIP is the nation’s largest flood insurance program with more than 5 million policyholders nationwide. Properties located in the 100-year flood zone with mortgages from government-backed lenders are required to have flood insurance.

While properties outside FEMA’s designated 100-year flood zone are not required to get flood insurance, it is recommended, though most people are not aware of the dangers of flooding in their neighborhoods, partly because of outdated flood maps and the absence of state laws requiring landlords to disclose flooding history to renters. That’s one reason why about 80% of flood victims after Harvey did not have flood insurance. Affordability also plays a major role in whether one secures insurance — low-income households, even those who live in the 100-year flood zone are less likely to carry flood insurance. In a nationwide analysis, FEMA found that even though 41% of households are low-income, they comprise 51% of households inside the 100-year flood zone without an NFIP policy.2

More than half of NFIP policies in Texas are issued in the Greater Houston area. There are nearly half a million active insurance policies for both residential and non-residential properties in the three-county region, the vast majority of which are in Harris County. About 15-16% of Harris County residents carry flood insurance through NFIP. In high-risk areas, that climbs to 28%.3

Local response to natural disasters in the Houston area

Local government plays a large role at the beginning of the disaster recovery process. In the immediate aftermath of a disaster, local governments establish shelters, provide basic necessities, coordinate and conduct rescues, and clean up and remove debris.

Local municipalities and districts also play a large role in mitigating the effects prior to the occurrence of disasters through investments in infrastructure and the adoption and enforcement of flood plain management policies. However, a majority of residents don’t believe the local government is successful in protecting their homes from flooding.

Six months after the flooding in Houston caused by Hurricane Harvey, about 40% of people in the region rated efforts by the local government to protect homes from flooding as “poor,” according to the Kinder Institute’s 2018 Houston Area Survey. Residents in Harris County have slightly more confidence in local governments than those in Fort Bend or Montgomery counties. Additionally, nearly half of both Black (49%) and white (45%) residents in the three-county region rated local government efforts as “poor.”

Buyouts

One method local governments use to mitigate the impact of future disasters is through property buyouts. The buyout program uses federal and local dollars to purchase properties in qualifying areas that have been flooded or affected by other natural disasters multiple times. Then, the land is used as parks, green space, or flood storage or overflow. Eligible properties include single-family homes, commercial buildings, places of worship and multi-family residences, but residential properties are the highest priority. This benefit is available to property owners only. If multi-family properties are bought out, the funds go to the owners, and tenants are required to leave. The average buyout takes longer than five years4 and only one in five typically qualifies.5

Harris County has used the buyout program more than any county in the nation. Harris County Flood Control District has spent roughly $342 million to purchase about 3,100 homes since 1985, according to a 2017 ProPublica report. There are still approximately 3,300 homes on the District’s priority-buyout list, which represents about 20% of homeowners who have volunteered.

Between 1995 and 2016, 2,400 properties were bought out, according to FEMA data reported by NPR, among which nearly 90% occurred in Harris County (2,092). An additional 290 buyouts took place in Montgomery County and 18 in Fort Bend. More recent data from Harris County Flood Control District shows an additional 576 properties have been purchased and 695 buyouts are in process since 2017.

Buyouts are concentrated in areas that experience multiple floods to maximize the effectiveness of the strategy. Buyouts in Harris County have concentrated in Jersey Village (430 buyouts between 1995 and 2016), East Aldine (132), Acres Homes (130), Greenspoint (121), George Bush Intercontinental Airport (119), and Kingwood (114). Buyouts in Montgomery County have been concentrated in Conroe (158). Fort Bend used the buyout program in 2016 to convert eight properties in Simonton to vacant land.

Private philanthropic response to natural disasters in the Houston area

The public sector plays the largest role in natural disaster recovery and response, though it can take time for public dollars to trickle down to individuals. Private philanthropic dollars often support an immediate response — including filling gaps in assistance for the most vulnerable — but philanthropy can also invest in innovative models of program and service delivery.

Between 2011 and 2019, about $202.6 million philanthropic dollars have been invested in Houston’s three-county region — the vast majority went to organizations based in Harris County, according to data from Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy. Over the past decade, disaster philanthropy in the region peaked in 2017 and 2018, with foundations, business and individuals investing $75.8 and $82.3 million in the region, respectively.

Nonprofits in Houston that have been top recipients of disaster philanthropy between 2011 and 2019 include Attack Poverty, Fort Bend Family Health Center, and Focus Humanitarian Assistance USA in Fort Bend County; United Way of Greater Houston, BakerRipley, and Greater Houston Community Foundation in Harris County; and Connect Outreach, Missions on Wheels, and Habitat for Humanity in Montgomery County, according to data from Candid.

An analysis by the Houston Chronicle found that nearly $1 billion was donated after Hurricane Harvey — the most on record after a disaster. That includes $522.7 million by the Red Cross; $114 million by the Greater Houston Community Foundation; $100 million by the Rebuild Texas Fund; $87.5 million by the evangelical group Samaritan’s Purse; $61.4 million by United Way; $41.6 million by JJ Watt’s campaign; $30 million by the Salvation Army; and $14 million by the Center for Disaster Philanthropy. A Charity Navigator report found 5.4 million people donated $742.6 million specifically for Hurricane Harvey relief.

Slow and uneven natural disaster recovery in the Houston area

Some residents in our region are not only hit harder by natural disasters in Houston, but also receive less assistance to recover. Research indicates that federal disaster assistance policies tend to place vulnerable groups at a disadvantage and reduce their ability to access resources and assistance for natural disaster recovery.6 As a result, the many impacts of disasters can last more than several years for those with the fewest resources needed to recover. Disasters can also widen the wealth gap. Joint research between Rice University and the University of Pittsburgh found that whites accumulated more wealth after natural disasters between 1999 and 2013 while residents of color accumulated less, even after controlling for a variety of demographic and household factors.7 In Harris County, the disaster-related increase in the Black-white wealth gap averaged $87,000.

Has Houston recovered from Harvey?

Data from the Episcopal Health Foundation’s Harvey survey found that Black, low-income and immigrant families were most likely to report they were not getting the help they needed to recover after Hurricane Harvey, and the financial assistance they did receive (if any) covered “very little” or “none” of their financial losses.

About 41% of Black residents who were affected by Hurricane Harvey reported that their lives were still “somewhat” or “very” disrupted one year later, compared to 26% of white residents. Nearly one in five (17%) Harris County residents reported their overall quality of life one year after the storm is worse as a direct result of Hurricane Harvey, with Black (31%) and low-income households (20%) reporting higher levels of disruption than the region overall.

Learn about social vulnerability and the Social Vulnerability Index

Helpful Articles by Understanding Houston:

- Houston is Resilient

- Houston is Generous